On 2020’s folklore, Taylor Swift compared herself to a mirrorball — reflecting her audiences’ desires, changing every part of herself to entertain. Since the release of that album, Swift has surged to an unprecedented level of fame and success. Already a megastar, she is now midway through the highest-grossing tour of all time, in her most high-profile relationship in years, and recently won Album of the Year at the Grammys1. Since folklore came out less than four years ago, Swift has churned out seven more albums (three original and four re-recordings of her earlier albums) culminating in the release of The Tortured Poets Department last month. Over the past half-decade, Swift has come to feel oppressively omnipresent, seemingly unavoidable even in conversations about climate, the economy, and sports.

In this context, Swift’s latest album gives the impression not of a mirrorball but of a funhouse hall of mirrors. Everywhere one turns, Swift is there, and this ubiquity2 threatens to suffocate her music. As Tom Breihan put it in his (excellent) review of The Tortured Poets Department, “the lore [of Swift’s life] has come to swallow the music.” Listening to the album, I felt overwhelmed — by its sheer length, by the weight of all that lore, by the baggage I bring from my own perceptions of and relationship to Swift’s persona and music. I’ve tried to separate Swift’s music from everything around it, and I’ve failed. What follows is my attempt to unpack this album and the metatextual albatross tied around its neck.

I did not particularly enjoy this album, partially due to personal preference. I’m generally drawn to music because of production rather than lyrics — I like songs that are sonically interesting, innovative, even chaotic and messy. I tend to not fully absorb lyrics, sometimes hearing a song dozens of times before processing what it is actually saying. Production-wise, The Tortured Poets Department shares much of the same synth pop DNA as Swift’s last non-rerecorded album Midnights. I’m not a full-fledged Jack Antonoff hater3; when he works with artists who have a strong sonic vision, I find his work inoffensive at worst. Swift, though, is much more a writer than a producer, and tends to derive the sound of her albums primarily from her producers. A decade into her collaboration with Antonoff, that sound is not growing any fresher, and the sleepy quality of Aaron Dessner’s contributions do little to liven up the album’s sound.

The stale and staid production may be less of an issue were it not spread across 31 songs. According to Swift herself, she began working on this album immediately after finishing Midnights two years ago. Based on this timeline, she and her collaborators wrote 31 songs in less than 104 weeks, which would give, at absolute most, 3.35 weeks per song, without considering however far in advance she might have completed the album. Swift was also preparing for the Eras tour and subsequently performing during 26 of those weeks, as well as breaking up with Joe Alwyn, dating Matty Healy, commuting back and forth to football games for Travis Kelce, and doing all the other work required to fulfill the job of being Taylor Swift. I’m no expert, but this doesn’t strike me as an ideal amount of time to produce 31 strong, polished songs.

Some people may respond to this critique by saying that The Tortured Poets Department was meant to be messy, raw, confessional — Swift is using songwriting as a diary to express her thoughts and feelings as they occur, no matter how unflattering, rather than saving them and refining them into polished pop products. My instinctive response to this defence is a quote from the great Cyril Woodcock of Phantom Thread fame4:

I frankly do not care if she is expressing her deepest, most personal thoughts in their rawest form when the resulting music is this uninteresting. Again, my gut reaction may not be entirely fair; it may be a simple matter of preference. I love pop music, and I tend to struggle with indie singer-songwriter-y types, but just because I find something uninteresting doesn’t mean it’s inherently bad; not all art is made for me and I don’t have to enjoy all art. The issue here is that I do feel Swift’s greatest strength is as a pop songwriter — melodies that stubbornly worm their way into your mind, clever turns of phrase, spinning archetypes and conventions into something new. Listening to The Tortured Poets Department, those are the elements that stand out — the rhythm and sound of the lyrics on “Down Bad” more so than their meaning5; the alliteration of “splintered back in winter, silent dinners” in the “Fresh Out the Slammer” or “hand on the throttle, thought I caught lightning in a bottle” in “The Prophecy”; pretty much all of “The Bolter”; the production on the second half of the bridge in “imgonnagetyouback.” But while these pop elements occasionally shine through, they more often fade into the background in favour of lyrical content that is equal parts embarrassing, frustrating, and forgettable.

Again, the album’s length does no favours in bolstering its lyrical content. Far too many of the songs are about the same relationship — even setting aside any external knowledge of Matty Healy (as I often wish I could), this album evidently contains song after song about a relationship that is shitty but not in a particularly remarkable way. Swift certainly has an ability to craft excellent songs from material that may be uninspired in another’s hands, but there is a limit to how many times even she can find an interesting way to talk about a relatively uninteresting relationship. It’s noteworthy how few songs on the album seem to be about Swift’s six-year relationship with Joe Alwyn, and the relative sparseness of these songs may have something to do with their higher quality — both “loml” and “So Long London” are quite gorgeous songs, capturing simultaneous resignation and respect at the end of a significant relationship. Unfortunately, the album contains far more, for lack of a better term, Healy songs. These tracks attempt to wring more material from a shorter timeframe, resulting in a series of amorphous songs that frequently have interesting moments but rarely feel complete. The best of the bunch is “But Daddy I Love Him,” in which Swift returns to imagery of archetypal Americana, a sort of sequel to Fearless’s “Love Story.” The song is a breath of fresh air — a song that is probably about Swift’s relationship with Healy, but doesn’t rely on the overt references (“Lucy” and “Jack” on the title track; “Blue Nile” and “Downtown Lights” on “Guilty as Sin?”) that make other songs on the album feel more like pleas for decoding. Like “The Bolter,” a similarly refreshing track later on the album, “But Daddy I Love Him” allows Swift to get outside of herself, to escape the hall of mirrors for a few minutes and sing from the perspective of someone who could be Taylor Swift, but could just as easily be someone who doesn’t have to bear the burden of being Taylor Swift.

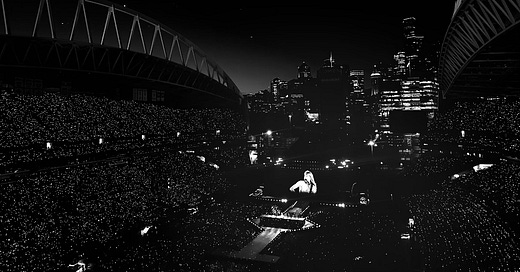

The burden of being Taylor Swift is perhaps the theme that recurs most across The Tortured Poets Department. Swift sings about the trappings of fame in several songs on the album, most notably “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?,” “I Can Do It With A Broken Heart,” and the aforementioned “But Daddy I Love Him.” Swift used to be tame, she tells us, “til the circus life made [her] mean.” “Judgmental creeps” and “wine moms” put her on a pedestal and judge her for the slightest misstep. She’s “miserable” and “depressed,” but she won’t let it stop her from putting on a show. These are the parts of the album I find most frustrating, at times even insufferable. I don’t want to gatekeep sadness, and I certainly wouldn’t want the level of constant fame and attention that Swift has. My issue is that Swift so clearly desires this constant fame and attention — anyone who has been to the Eras tour can confirm that she positively basks in the audience’s adoration — and has worked extremely hard for decades to build and maintain this status. None of her actions over the past year suggest that this has changed; in fact, she appears hungrier than ever6. Swift’s relationship with Alwyn was incredibly private, and she showed a remarkable ability to evade attention through much of the relationship. Her relationship with Travis Kelce is the polar opposite, seemingly conducted almost entirely on display. It’s absolutely ludicrous to hear someone in her position, who recently became a billionaire and shows little indication of stepping away from the spotlight anytime soon, sing, “don’t want money, just want someone who wants my company” — particularly when that someone has aggressively marketed several different “limited” physical releases in a clear effort to boost sales as much as humanly possible. Swift lashes out at her fans (and audiences in general) on “But Daddy I Love Him” and “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?”, but doesn’t appear keen to reckon with the role she’s played in stoking modern fandom, including her own maniacal Swifties. Swift acknowledged in 2019 that she had “trained” her fans to decode the clues about her life and career strewn throughout her work; intense interest in her personal life is a natural byproduct of this training, for all she decries it on this album.

I kept thinking about Britney Spears’ “Piece of Me” while listening to the fame-oriented tracks on The Tortured Poets Department7. Much like Swift on The Tortured Poets Department, “Piece of Me” sees Spears lashing out at audiences and at the magnitude of her own fame. Swift herself referenced the song in 2017’s “Look What You Made Me Do,” with the lyric “The world moves on, another day, another drama, drama / But not for me, not for me, all I think about is karma” alluding to “I’m Miss Bad Media Karma / Another day, another drama” on “Piece of Me.” So what makes “Piece of Me” work while similar themes on The Tortured Poets Department fall so flat? I think there are several reasons, beginning with the track itself. The production on “Piece of Me” is heavy, abrasive, chaotic. Spears’ voice is distorted, pitched up and down at different moments. When she delivers the title lyric “You want a piece of me?”, she sounds venomous, angry, fed up with fame and attention, and the song’s production matches her tone. “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me?” may the most equivalent song on The Tortured Poets Department, but its production is virtually indistinguishable from the rest of the album; while Swift’s vocals are more impassioned than on other tracks, the song’s production makes it feels safe and palatable, diluting the effect of its lyrics.

The metatextual context of “Piece of Me” also sharply contrasts The Tortured Poets Department. Whereas Swift has appeared to be on top of the world for the past several years, Spears was far from it when “Piece of Me” came out. The song was the second single from Spears’ magnum opus Blackout, which launched on October 30, 2007. Spears’ management company had terminated her as a client slightly over a month earlier; Rolling Stone’s February 2008 cover story on Spears noted that, at the time of writing, she had no manager, agent, publicist, stylist, image consultant, crisis control manager, or driver. While Blackout as an album is undoubtedly a product of pop machinery, its release came at a time when Spears was in a state of active rebellion — against her family, against the music industry, against the media8. There was very little promotion for the album, and there would certainly be no tour. Spears was actively lashing out at the forces that had pushed her to superstardom, and as a result she experienced legal, financial, and personal consequences that reverberated for over a decade9. In this context, “Piece of Me” sounds almost brave — Spears revels in her uncomfortable and often unflattering actions (many of which are documented in the Rolling Stone piece), and the track’s ire reflects her broader frustration with an industry that built her and then built itself around her.

Compare this to the release of The Tortured Poets Department — an album announced at the arguable peak of Swift’s career, accompanied by robust (even aggressive) marketing, which then broke countless sales and streaming records upon release and was deemed an “Instant Classic” by Rolling Stone10. On her recent tour dates, Swift dedicated a new section of the show to songs from the album, including “Who’s Afraid of Little Old Me” and “I Can Do It with a Broken Heart.” Swift unveiling elaborate performances for these songs only drives home why “Piece of Me” works and these songs do not. For Swift, at least at this point in her career, vulnerability can only be expressed in a finely-tuned, pre-rehearsed manner, and only when it is coated in a veneer of self-awareness. For all The Tortured Poets Department purports to be messy and unrefined (and certainly is musically), in terms of Swift’s image it is as carefully considered as anything else in her career; while she might express discontent with parts of her success and the music industry, that discontent is not enough to outweigh her immense desire for fame and for the benefits it offers her. Spears had more or less checked out of the music industry in 2007 (before being quickly brought back in after the implementation of her conservatorship in early 2008); Swift has never been more dialled in.

That’s not to say that I want Swift to go through what Spears did; I really, truly would not wish that on my worst enemy. I am also sure that Swift has complicated feelings about her fame and success, and is sad even when she is on top of the world, and that’s fine. It’s just that, when you release a song like “I Can Do It With A Broken Heart,” a song that critiques the pressures of the music industry and of fame and of immense popularity, and satirizes your own ability to work through your pain, and then you turn around and put on a seamlessly staged performance of that song on your billion-dollar-grossing tour, and show no sign of actually addressing or changing what you critique in yourself and in your industry… Well, to me, that comes across as less of a critique and more of a celebration — of yourself, and of capitalism, and of the millions of people who clamour for your love and attention, and of the empire you built and the power you wield. It is the illusion of vulnerability with no sacrifice, no culpability, no stakes; Swift can sing about her sadness and her anger and her disillusionment, and her profits will just keep going up. It’s become increasingly clear that my artistic wishes for Taylor Swift are not the same as her own goals — she is focused on profit more than on anything else, and she is not willing to risk jeopardizing those profits. On some level, I don’t have an issue with that. If Swift doesn’t want to be truly vulnerable, or to put effort into changing the status quo, that’s fine — I don’t expect that from pop musicians. But to be a pop musician (or at least a pop musician whom I would enjoy listening to), she would need to put out some good music instead of the sanctimonious wallowing that dominates The Tortured Poets Department. If Blackout didn’t have “Piece of Me,” I would still love the album. Why? Because it has really fun, innovative, excellently produced songs with largely nonsensical lyrics. I would much prefer standout pop music — from Swift or from any other musician — than music that has the sheen of earnest vulnerability concealing little more than fuzzy synths and a thesaurus.

All this probably makes it sound like I hate the album. I did the first time I listened, but I don’t really anymore. I don’t mind the songs when they come on, and even enjoy some of them, but will not actively seek out most of them, and as a unit they blend together in a haze of mediocrity. In my favourite piece of writing about Taylor Swift, “I Have Never Not Thought About Taylor Swift,” Nicole Linh Anderson writes that Swift “is an empty vessel onto which we project our own beliefs and assumptions about the broader world.” I strongly believe that Swift is capable of something great — greater than anything she has released to date. It’s become increasingly clear, however, that my desires and expectations for Swift’s music do not align with her own, and I’m beginning to wonder if my own belief might be ill-founded.

Oh well. There’s still plenty of time to be proven right (or wrong). At the end of her piece, Anderson asks if she will be thinking about Swift for the rest of her life, and my answer is the same as hers: “Probably.” In the meantime, I will just keep listening to Blackout.

For 2022’s profoundly mediocre Midnights.

Which is overwhelming even as someone who loves much of her music!

Although I think he should perhaps take a nice long well-deserved vacation.

In case you were wondering, “The Smallest Man Who Ever Lived” is clearly the most Phantom Thread-coded song on the album. Major “Are you a special agent sent here to ruin my evening and possibly my entire life?” energy.

I wrote “if it were in Simlish I would like it” in my notes while listening to “Down Bad.”

Which I don’t really have a problem with until you release an album on which you repeatedly lament your fame and success.

Partially because I wished I was listening to “Piece of Me” instead.

Though her relationship with the press was not always antagonistic — she sold her wedding and baby photos to People and was dating a paparazzo at the time of the Rolling Stone cover — it was certainly parasitic and exploitative. In 2007 alone, photo agency X17 grossed an estimated $2.5 million from photos of Spears, and had a team dedicated to tailing her 24 hours a day.

I do want to acknowledge that there were likely other factors (ie. mental health, etc.) at play here, but it is also clear that Spears did wish to rebel against her family, label, and others, and the public does not have confirmation of what other factors might have been at play.

Deeply embarrassing.